This week, the Guardian published a long article entitled “Venezuela’s Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra at 50: is it time for brickbats or bouquets?” Despite the title’s implication of an even-handed assessment of pros and cons, there was never any doubt which way the article was going to fall, given that it was written by Marshall Marcus, the founder and president of Sistema Europe and one of the most prominent advocates for Venezuela’s El Sistema, for which he has also worked. In the interests of balance, I will address some of the omissions and questionable statements in his article, which is better understood as El Sistema PR rather than journalism.

Marcus’s central aim is to contest the accusations (made in a separate Guardian article) that El Sistema’s touring orchestra, the Simón Bolívar, serves to art-wash the Venezuelan regime of Nicolás Maduro, now a fully-fledged dictatorship. Marcus acknowledges briefly that El Sistema “sits under the office of the president and that its board of directors includes high-profile government politicians,” but he moves on swiftly to try to undermine the argument that the orchestra has become a propaganda tool.

In hundreds of concerts within the country and across the world, I am yet to see the presence of a single government figure, apart from perhaps on one occasion in Caracas (and that was to praise El Sistema with no mention of the government). Abroad, never. If the government is trying to use Dudamel or the orchestras as puppets or henchmen, someone needs to give them the ‘how to’ handbook.

He is more sympathetic to the argument that “El Sistema is a product and symbol of the country not the government, and that it existed for several decades before the current presidential incumbent.”

First, the facts. Under Chávez and Maduro, El Sistema was moved first to the Vice-Presidency and then to the Office of the President. In 2018, Maduro’s right-hand woman (Delcy Rodríguez) and his son (Nicolás Jr) were appointed to El Sistema’s board of directors. These facts speak unequivocally to the regime’s desire to bring El Sistema under closer political control. Yes, El Sistema predates Chavismo; but the program’s current operation is unlike anything before Chavismo. Should there be any lingering doubts about the government’s soft-power intentions, they are dispelled by President Maduro’s statement in 2017 that he was assigning $9 million – in the depths of Venezuela’s economic crisis – to El Sistema’s orchestral tours “to enamour the world.” For a country’s president to announce funding for an orchestral tour is hardly an everyday occurrence.

Pace Marcus, examples of government figures at concerts abound. I mentioned one, involving none other than Maduro, in my 2014 book El Sistema: Orchestrating Venezuela’s Youth, which Marcus has read:

Abreu lent his support to the government’s presentation of its record to the UN’s Human Rights Council. “‘We will demonstrate that Venezuela is a country that has managed to undergo a profound revolution to construct socialism via the path of freedom of expression, the debate of ideas, education for life and for the freedom of our people,’ affirmed the Minister for External Relations, Nicolás Maduro. These declarations were offered moments before attending the concert named ‘So That Humanity May Be Human,’ offered by the SBYO in Geneva” (“Maduro” 2011).

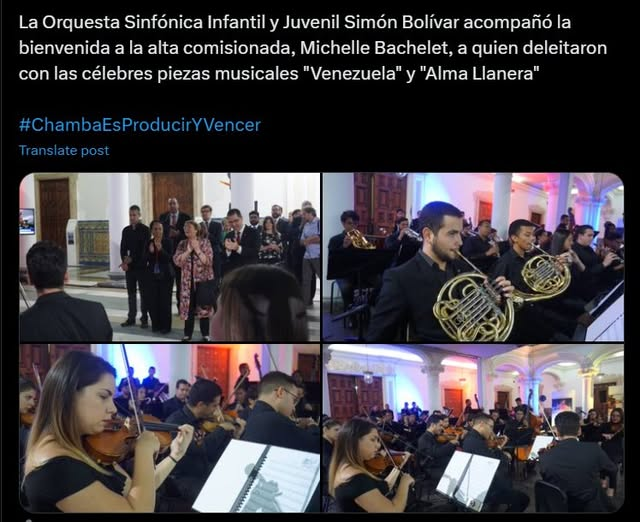

There are other examples of the Simón Bolívar orchestra accompanying political missions to the UN, for example operating alongside Delcy Rodríguez in 2016. The orchestra was wheeled out “as a sign of fraternity and Bolivarian peaceful diplomacy” to try to sway the UN’s Michelle Bachelet when she visited Venezuela to research her human rights report in 2019. It was employed in an anti-Obama propaganda video in 2015. The list could easily go on, but the point is already clear: the Venezuelan government has had the “how-to handbook” for at least 15 years and has been using it assiduously.

And the thing is, it works. Take this review of the SBSO’s first London concert:

After the full orchestra came together for the resonant ending, in which Dudamel’s movements powerfully echoed those of the timpani players, the whole audience rose to its feet for a moment that felt like everything to do with freedom and little to do with dictatorship.

This is art-washing, live, in real time. And this is why an authoritarian president pays such close attention to orchestral tours, why his regime funds them to the tune of millions of dollars. In the light of such a review, art-washing looks like a wise investment.

On this issue, El Sistema’s most prominent critic has been the pianist Gabriela Montero. Marcus notes:

Montero clearly has support, but many in Venezuela, including those critical of the government, disagree with her. Anaisa Rodriguez, for example, responded in Noticiero Digital, a well-known Venezuelan news site often critical of the government, “[Montero’s] words filled numerous people with indignation who have no links with ‘Chavismo’.”

In the interests of balance, we should also note that many in Venezuela agree with her, such as Jorge Alejandro Rodríguez, writing for Tal Cual Digital:

El Sistema, once a symbol of hope and social transformation, has become the perfect whitewashing tool for an unpresentable regime that perpetuates suffering. Dudamel, with his undisputed virtuosity, has preferred the comfort of silence to the urgency of a pronouncement. His refusal to condemn the atrocities committed by the Venezuelan regime is not neutral; it is, in fact, a position that benefits the oppressors. This ethical vacuum is magnified when compared to figures who, in similar situations, used their platform to defend universal principles.

***

Much of the rest of the article is a spirited defence of El Sistema that dances around the copious research on the topic, always aware of it, never referencing it directly, sometimes alluding to it and sometimes pointedly ignoring it. It is a dance that few readers will notice, so it’s worth examining it here.

“El Sistema is a music programme with a methodology linked to personal and social development.”

Not really. El Sistema is a music programme designed to train orchestral musicians: “to produce musicians like sausages,” in the words of one of its members. The ideas about personal and social development were added two decades later, and for strategic reasons, as I have argued in my research for a number of years. They operate primarily at the level of discourse rather than practice. The Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) evaluator Eva Estrada wrote in 1997 that musicians “perceive contradictions between the stated values and the actual practices of El Sistema,” and of the 18 that she interviewed, 14 stated that the program “contradicts their expectations of professional and personal development.” El Sistema’s methodology, if one can call it that (something disputed by the eminent Argentinean music education scholar Ana Lucía Frega, who also evaluated El Sistema in the late 1990s), involves old-school drilling in technique and repertoire.

“The fact that many of the young musicians of the orchestra seemed to come from deeply disadvantaged social backgrounds made their success all the more awe-inspiring. Here was a model for how music really changed lives.”

This is cleverly written, with the word “seemed” doing a lot of work. The average reader probably won’t even notice it – but Marcus presumably put it there because he knows that the IDB’s biggest evaluation in 2017 found that only a small minority of El Sistema students (fewer than 17%) actually came from such backgrounds. Including this fact would ruin the whole story, but omitting it altogether would be dishonest. So Marcus opts for “seemed” – a sleight of hand that allows the valuable myth of “saving kids from the slums” to continue to float in the air, but with an almost imperceptible get-out clause.

“Reports of an oppressive regime and a boot-camp mentality in the nucleos were compounded when allegations about a specific case of sexual harassment surfaced in the spring of 2021. There was immediately the question, was this a one-off – in which case it was still extremely serious – or was it a sign of something even worse – a generalised practice and culture?

To their credit El Sistema Venezuela appear to have taken very seriously the sexual harassment allegations.”

Again, it is worth stating the facts. There were two specific cases, not one – and one of the accusers claimed explicitly that her experience was part of a generalised practice and culture. As we reported in the Washington Post, the former El Sistema musician Angie Cantero posted a public story on social media, saying that El Sistema “was / is plagued by pedophiles, pederasts, and an untold number of people who have committed the crime of statutory rape.” Behind its attractive façade, she alleged, “there are a lot of disgusting people who love to deceive girls and teenagers, taking advantage of their position of power and renown within El Sistema.” Many of the commenters backed up Cantero’s allegations, based on their own experience.

Cantero’s allegation of a generalised problem is supported by the testimony of another former El Sistema musician, Luigi Mazzocchi, who affirmed in a VAN Magazine article in 2016 that teacher-student relationships were “the norm.” I, too, had described a pervasive problem in my 2014 book. There were also four published investigations of sexual abuse in El Sistema in 2021, by journalists from four countries, and all supported Cantero’s allegations. In short, there is ample evidence already in the public realm to answer Marcus’s question and therefore no justification for leaving it unanswered, which appears to be an unwarranted attempt to sow doubt.

In 2014, far from taking my allegations “very seriously,” El Sistema described them as “absolutely false.” No significant actions were taken for the next seven years. The consequences of this inaction were pinpointed by “Lisa”, one of the sexual abuse survivors whose testimony was central to El Sistema’s #MeToo moment in 2021:

I wonder why they waited so long. This isn’t new. I just presented my testimonial [in 2021], but in 2014 Geoff Baker published a book where he described the structures at El Sistema that allow the abuse, and concrete cases he collected in his interviews. Baker’s book was read, in Venezuela and abroad, as an attack against El Sistema. But at that moment I was being abused in the institution. If they would have taken action then, I would have been protected, as well as other people.

Whether even the 2021 institutional response should be considered “very serious” is a matter that I have examined previously.

In terms of El Sistema’s social impact, Marcus argues that “we should not forget the profound effect the training and methodology has had on millions of Venezuelans.” This statement is crying out for some supporting research, but instead we get one personal experience and an impressionistic view from an American previously unfamiliar with both Venezuela and El Sistema, whose opinion was formed after 10 minutes’ exposure. Neither tells us anything about the effect of El Sistema on millions of Venezuelans. For that, the best source we have is again the IDB’s 2017 evaluation, which found that, even if one squinted at the data through a particularly flattering lens, the effect appeared to be small. The researchers found no evidence that El Sistema had an effect on cognitive or prosocial skills, and taking into account their findings about the low poverty rate among El Sistema entrants, they concluded that their study “highlights the challenges of targeting interventions towards vulnerable groups of children in the context of a voluntary social program.” And this view came from El Sistema’s major non-governmental funder and supporter. Using a more robust methodology, the effect actually appears to be zero.

The article finishes by speaking directly to (and for) the orchestra’s musicians:

“in the midst of this clamour, the one voice I do not hear is that of the orchestra’s musicians. They are here in Europe to make music, to celebrate an anniversary and show what their training has done for them and their country, yet some people in the papers and on social media seem to be trying to use them as convenient puppets in a fight with the Venezuelan government.

So, as a musician, my last words go to the young Simón Bolívar musicians on stage: cut out the white noise, hold your heads up high, and show what you can do. You are yourselves. Only be that, and your concerts will be the amazing success they deserve to be.“

There are two inconvenient truths here. First, the orchestra’s current musicians are kept on a very tight leash and would not be allowed to speak freely and independently to the media. Indeed, one of the criticisms that I and others have made is that El Sistema marginalizes and suppresses the voices of its members. Second, in actual fact the voices of former El Sistema musicians – now off the leash – were heard loud and clear just the previous week, in Jessica Duchen’s article on El Sistema in the Times. It’s surprising that Marcus didn’t hear them, given that it was a major article in a major newspaper and received a lot of attention due to its highly critical take. Perhaps he chose not to hear them, as their message (summarized as “corruption, abuse, propaganda”) would have blown another gaping hole in his boosterish article.

And then, what is the “white noise” that is to be cut out? Nothing other than the public debate about the role of musicians in society, and about the complex connection between El Sistema and Venezuela’s slide into dictatorship, which is much discussed at home and abroad. The longstanding questions about how artists should respond to tyranny. The kinds of questions that any thinking, ethically responsible musician ought to engage with, whatever conclusion they may ultimately draw.

Marcus is a prominent advocate for El Sistema’s “social action through music,” which proclaims loudly that it forms good citizens, yet here he proposes not only inaction but even total disengagement with discussion about civic responsibilities, rights, and actions – discussion that could not be more important or urgent right now, given current political events in Venezuela.

I recently attended the Social Impact of Making Music (SIMM) symposium in Copenhagen and saw how higher music education is grappling with how to make its work more reflective and socially engaged. It is exploring notions like “artistic citizenship” and “musicians as makers in society” in an effort to connect music education more deeply to the problems and concerns of our time. Attempting to tackle such knotty issues is the broader direction of travel among leaders and educators concerned with music’s social role, yet Marcus urges El Sistema to head in the opposite direction – away from the difficult questions and the public debate, and back to the stance of a previous era when a musician’s job was just to play the notes.

Not for the first time, El Sistema and its advocates appear remarkably out of sync with progressive tendencies in music education and with sectors like socially-engaged arts and community music, with which it shares some superficial similarities (mainly rhetorical) but few philosophical underpinnings. Indeed, El Sistema embodies the democratization of culture to which community music’s cultural democracy is a critical response. As I have argued before, El Sistema represents less a revolution in music education than a counterreformation: in the memorable words of the musicologist Robert Fink, a “visit from the ghost of public-school orchestra rooms past.”

On the basis of this article, it seems that Marshall Marcus’s faith will not be swayed by any amount of evidence – not just the corruption, abuse, and propaganda that Duchen is simply the most recent writer to detail, but also well documented problems ranging from bullying of students, to lies over founder José Antonio Abreu’s qualifications, to El Sistema’s absolute failure to achieve its primary organizational goal over the last three decades (decentralization). As a result, the vast majority of El Sistema’s “out-of-tune notes” are missing from his account. The general public, however, deserves a more accurate analysis.