In a recent study carried out in Colombia, Cespedes-Guevara and Dibben (2021) found that a year of training in a classical music instrumental program had no significant effect on prosociality or empathy. Their results echo those of other studies of similar programs, such as Alemán et al. (2017) on El Sistema in Venezuela, and Ilari et al. (2018) on an El Sistema-inspired program in the US.

Does this mean that music education doesn’t foster prosociality and empathy? No. There are other studies that suggest the opposite, such as Rabinowitch (2012) and Van der Vyver et al. (2019). But these studies involve musical activities and games that were expressly designed to promote prosociality or empathy. The null outcomes emerged from more conventional music education programs like El Sistema. The conclusion is clear: music making that is shaped with prosocial goals in mind is more likely to achieve those goals than conventional activities like playing in a youth orchestra. This is perhaps an unsurprising conclusion, yet it is one that poses a challenge to the social action through music (SATM) field, which is founded on El Sistema’s reading of conventional musical training through a social lens rather than designing of music education to maximize social impact.

Ilari et al. arrived at the same point. They note that “effects of music education on children’s social skills have been found mainly in programs that followed specialized curricula,” and

“for music education programs to be effective in developing social skills, perhaps it is necessary to devise curricula that not only break down traditional hierarchies found in collective musical experiences, but also afford children ample opportunities to exercise social skills such as empathy, theory of mind, and prosociality in more direct ways.”

In a more recent article on the potential of music to effect social change, Rabinowitch (2020) explores this idea further. She asks:

What if we could intentionally “engineer” new forms of music or music-making designed to maximise the positive effects of music on social skills?

She suggests that “in order to optimise its social impact, engineered music-making should involve informal, even improvisational, highly mutualistic joint performance,” and that it would be advisable to emphasize collaboration rather than competition.

“It might be similarly important to focus on the process of creating music rather than on its end result. That is, the aim of the activity might not be to produce a well-polished concert, but to participate in the music-making”

These studies thus provide a clear steer away from SATM’s historical roots in concert performance of canonical orchestral repertoire, and towards more innovative design.

Urging the field to put social objectives at the heart of practice as well as discourse was one of the key messages of my most recent book, Rethinking Social Action Through Music. There are other ways that Cespedes-Guevara and Dibben’s study intersects with my own – perhaps unsurprisingly, given that both looked at SATM in Colombia. Theirs included a comparative element, involving also dance and sport programs. They observed a difference between the young musicians and footballers, which was signalled to them by the director of a music program:

Regarding violence prevention and community transformation, the children in the football programme are more concerned with transforming the dynamics of violence in their territory; those of the orchestra are more oriented to their own life project. We have tried to balance these things, because what we observe is that the orchestra children develop these skills very well and their life projects are very reflective and critical, but when it comes to thinking about their territory and influencing their territory to transform it, it’s not that strong.

(Director, industry-sponsored youth symphony orchestra)

Cespedes-Guevara and Dibben continue:

“Informants from the music-training projects described the individual transformation, whether actual or intended, as a journey away from the home community, and by implication its associated criminality and poverty, saying, for example, ‘that music, somehow, helps them escape’ (Director, infant and youth symphony orchestra), towards the world of music constructed as a particular orchestra and/or as the classical music world more generally: ‘…it was bringing the children closer to classical music… to bring these children from this community closer to the orchestra Philharmonic or classical music’ (Director, non-profit music school). Music and the community are constructed as two separate worlds, demarcated by music genres and associated lifestyles.”

The director of an orchestral program explained this last point:

“[W]hat this type of music does is to open themselves to a different world. So you see the young people who listen to reggaeton, who listen to other types of music, and these children from the foundation, I don’t claim that they don’t [listen to reggaeton], but they are more immersed in another style of music and in another lifestyle.”

Cespedes-Guevara and Dibben conclude:

If, as this implies, the two worlds are separate, transformations that take place for the individual stay with that individual rather than benefiting the community from which they come

Several themes may be drawn out here. First, for all the emphasis on collective music-making, SATM appears to be an individualizing process; and for all the talk of social change, SATM seems to promote escaping from social problems rather than facing them. Cespedes-Guevara and Dibben found that young footballers were more committed to transforming their community than young classical musicians. The prosociality and life-project findings might be seen as two sides of the same coin: if SATM fosters orientation to a personal life project, then it is hardly surprising that it does not promote prosociality.

There are close parallels with my argument in my book:

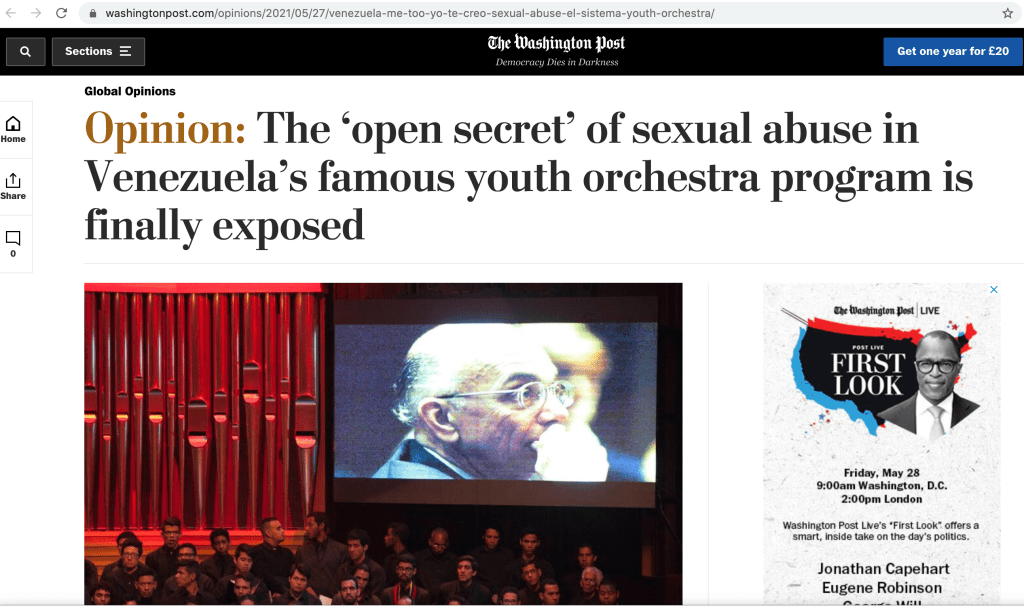

the figures at the top of the SATM pantheon—particularly conductors like Gustavo Dudamel—are those who have established themselves in orchestras overseas; they symbolize an ideology of music as a means of individual social mobility and transcending the local, rather than as a catalyst for collective social change within and for the community. Here we see a paradox in orthodox SATM: an idealization of the collective (the orchestra), yet an individualized conception of success (the young musician who “makes it” in the profession).

Among the mistranslations that occurred when SATM was adopted in the global North after 2007 was to describe it using the language of social change, when in reality the field’s “social turn” in Latin America in the 1990s was underpinned by the notion of social mobility.

A lack of territorial connection and commitment was recognized as a significant weakness by the leaders of the Red de Escuelas de Música de Medellín during my fieldwork, and they addressed it by converting the program’s social team into a territorial team.

Next, Cespedes-Guevara and Dibben’s argument about SATM fostering social separation, mediated by musical genre, finds a close echo in my book, with its emphasis on classical music and boundary-drawing:

the characteristic dynamic of the collective in SATM is not the much-touted teamwork—of which the conductor-led orchestra is in fact a strikingly poor example—but rather tribalism.

I too observed the dichotomy of classical music and reggaetón. As I noted, a member of the Red’s social team characterized the attitude of some of the program’s students to their peers as

you, so simpleminded, just listening to reggaetón and me, so sophisticated, listening to Beethoven

The fact that our two studies independently came up with similar findings from similar programs in different Colombian cities is undoubtedly suggestive.

Cespedes-Guevara and Dibben note two points of interest – or perhaps, two sources of tension – for critical researchers of socially-oriented music education: (1) with music widely assumed to do good, neither practitioners nor sponsors are necessarily interested in research on the social impact of such programs; (2) the more specific assumption that classical music is particularly good (i.e. better than other genres) clashes with research into the mixed effects of orchestral programs and with the obvious benefits of learning other musical skills, effectively bringing critical researchers into a relationship of tension with participants’ deeply held beliefs about music – a point that I made in my fourth chapter.

Finally, their article raises broad and important questions about the social impact of making music. As they note, “social impact” in SATM actually looks a lot like “individual impact” when viewed through the statements of those working in the field. Furthermore, researchers struggle with a similar issue: we like to talk about the social impact of making music, but social impact is extremely difficult to measure, and attributing it to a single intervention (such as a music program) is even harder – so we tend to study other things. As Cespedes-Guevara and Dibben put it:

it is notable that there is limited focus on the effects of these interventions beyond the individual: how do these programmes impact their families, neighbourhoods, cities and the nation? And to what extent can these impacts be captured by psychological instruments that focus on individual, short-term effects?

There is a challenge here for both practitioners and researchers of SATM, then. Are the work and the evaluation of the work really about social action at all? To expand on a point from my book (p. 206), is “social action through music” simply a misnomer for this field, given that its orthodox manifestations, at least, have little to do with either “social” or “action”?

To live up to its name, SATM may need to take two steps: adopt a more political approach (Dunphy 2018) and engage in more of Rabinowitch’s “engineering.”

References

Alemán, Xiomara, et al. 2017. “The Effects of Musical Training on Child Development: A Randomized Trial of El Sistema in Venezuela.” Prevention Science 18 (7): 865–78.

Cespedes-Guevara, Julian, and Nicola Dibben. 2021. “Promoting prosociality in Colombia: Is music more effective than other cultural interventions?” Musicae Scientiae.

Dunphy, Kim. 2018. “Theorizing Arts Participation as a Social Change Mechanism.” In The Oxford Handbook of Community Music, edited by Brydie-Leigh Bartleet and Lee Higgins, 301–21. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ilari, Beatriz, et al. 2018. “Entrainment, Theory of Mind, and Prosociality in Child Musicians.” Music & Science, February.

Rabinowitch, Tal-Chen. 2012. “Musical Games and Empathy.” Education and Health 30 (3): 80-84.

Rabinowitch, Tal-Chen. 2020. “The Potential of Music to Effect Social Change.” Music & Science.

Van de Vyver, Julie, et al. 2019. “Participatory arts interventions promote interpersonal and intergroup prosocial intentions in middle childhood.” Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 65.